If you’re going to take 4 months off, one thing’s for certain, you’re gonna think a lot about what you want to do with the time before you get it. Lots of folks would be drawn to the idea of travel or some other big adventure. That’s not me. Sure, there are a few things I thought about along those lines when staring out the office window, but I knew that I just wanted the time.

Years ago, I was at a post-work happy hour with the usual suspects. One of our number, Greg, was about to experience a life-changing event of a certain fashion: His wife was going to Europe for work for six weeks. “Greg! Whatever will you do??” was the question, where the askers were mainly thinking that Greg was going to get, well, how to say it… Lonely? Anyway, Greg’s mind was somewhere else entirely. His response was “I’m gonna do whatever I want to do, whenever I want to do it!” That struck me as sagely words at the time, and when I thought about the core plan for the summer, that was it.

That’s not to say I had no plan at all. No, I had a long list of stuff that I could do, some of which being really should do. But no particular order to it. Having a list like that is, I think a pretty important thing to have if you’ve got a bunch of unstructured time coming at you – else you can easily slip into habits like playing too many computer games, sleeping too much… It’s better to have that menu of things you could do at the ready. That’s not to say the only things I did were on that list – far from it, as it turns out, but the list was a good thing and I checked off most of the stuff on that list.

Let’s talk about what I didn’t do

So before we start – I think I really have to reaffirm that I didn’t travel. Had no plans to do it. I don’t enjoy airports even a little bit, and that downer kinda ruins long-distance travel for me. Further, I feel like if ever I want to see something new, I just have to look a little closer at something familiar. So there’s no draw there.

And alas, I wanted to spend more time hiking in the mountains than I did, but my wife has had some problems with hip bursitis that kept her from being able to go, and that pretty much ruined it for me. There’ll be other opportunities.

I also thought about flying quite a bit. Funny, though, I knew that I wasn’t in a position yet to commit to renewing my pilot’s license. That meant that if I went flying, it’d basically just be a joy ride, and that would probably be more bitter than sweet. What I enjoy about flying is the whole package – the technical challenge of it, the experience of doing it, and the utility of being able to travel without the unpleasantness of airlines. If I can’t have the package, well, it’s just not going to be the same.

So I thought instead to give glider-flying a try. That could serve more of a purpose as I’d get a chance to see if I liked it enough to pursue it more seriously later. But alas, the local glider club (for various reasons including the pandemic and runway repairs) couldn’t accommodate me this summer. Again, there’ll be other chances for that, so no tears.

Fixing Stuff Around the House

I really enjoy home-improvement work. I enjoy the challenge and the learnings and I get a lot of satisfaction out of it when I’m done, so it’s not surprising that it’s the biggest line-item.

The first thing I did was clean up and organize the garage shop. It’s funny that if you look at videos from people who make furniture like I do, it seems like almost half of them are for making stuff that’s just for the shop. Be it work benches, storage, whatever. I view that as a bit pathological – you want to be making furniture, not making stuff to make furniture. The trouble is, there’s a lot of inefficiencies built into my workspace that I never addressed because I always felt like I needed to focus what time I had on actually getting stuff done. Now that I got the time, I figured it was worth it to get after it.

So the first thing was just plain building up some shelves and such, reorganizing stuff around the shop and getting rid of some extra stuff.

One of the more amusing things I did was fully commit to labeling drawers and such with their content. My Dad was an absolute fiend for that kind of thing. I thought it was something he picked up in his old age or something, but when I was visiting the old homestead, my cousin showed me a piece of pegboard that came from the workshop that my Dad had carved out of Grandad’s garage when he was a kid. He had outlined the shape of all the tools and where they should go on the pegboard. I think that was a common thing back in the day. Still a pretty good idea, as least so long as the toolset you use stays constant, because, well, it turns out that paint can hang around a while.

Inside the house, my wife and I fixed up our front entryway. That involved taking down a popcorn ceiling treatment, fixing drywall, cleaning and painting. In this I found a way to like the setting type of drywall compound. It has these qualities that make it good for small jobs:

- It dries quicker, allowing you to be done with drywall within a day.

- The premixed stuff, if you open and close the bag a lot, tends to get little flakes of hardened drywall in it that cause mayhem. I definitely wish you could get it in smaller quantities.

- I wish you could get the setting compound in smaller batches as well, because it seems to have a shelf-life. The several-years-old bag SilverSet 40 now takes a couple hours to dry. Still faster than the boxed stuff, but it’s noticeable.

- The fast dry time enforces a certain cadence to your work, which is a good thing. When it comes to drywall, trying to fix a coat of it while it’s still wet is often counterproductive. Better to just let a mistake dry, sand it, and do better on the next coat.

- 40 minute set time is a good minimum, but what it does mean is that you have to clean your tools on every batch, and that’s a big cost.

We also got after the children’s bathroom, although we limited our ambitions there and didn’t touch the tub surround, which is definitely not great, but not seriously broken either. We also didn’t re-tile the floor, but my wife did put on some kind of dye for the grout. It was a very fussy job, but way, way less work than peeling off and re-tiling, and the tile wasn’t bad, it was just grungy grout.

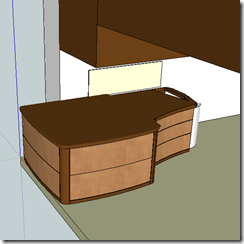

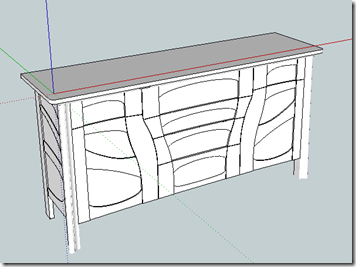

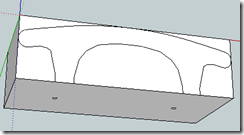

I built a new vanity, medicine cabinet, and mirror frame out of my dwindling stock of Walnut that I bought several years ago. Here I had some trouble with some Varathane poly. It didn’t dry properly and didn’t color the wood uniformly. For polyurethane, the accepted way to get rid of a can is to leave the lid off and let it harden. That can’s been sitting for weeks and has just barely even skinned over. I’m going back to Minwax.

We also did a lot of drywall fixes and Dianne had an adventure in wallpaper. Hopefully that stays looking nice, we’ll see how we do.

In my final week off, I redid the garage-side of the garage-to-house door. It’s always been pretty hi-howyadoin because the wall is pretty wonky and Bear, our house-monster, clawed the crap out of the trim and door frame.

I crafted up some custom molding from MDF and it looks, well, it’s okay. Nothing magical. But I did learn a new trick for MDF – if you just prime and paint the cut-end of MDF, you’ll get a texture like 60 grit sandpaper. You can beat this by a variety of ways – apparently oil-based primers help. Some say that Shellac-based primers work, but I’ve not had good results with that. What I tried this time was smearing a layer of wood glue. I used Titebond II, full strength. Some say you can thin it and paint it on. In any case, one coat of glue plus some sanding, plus priming, plus light sanding again made a good surface.

The other fun thing was fishing the control wire for the garage door opener behind the wall. It was made more challenging because the wall is insulated. We achieved success by using a craptastic endoscope that we bought last year. Dianne fitted the end with a hook and was able to guide it through, spot the fish tape and snag it with the hook.

Self-Improvement and the like

I’ve actually taken long breaks like this several times before. One of the hallmarks of them was that the first few weeks were often, to my mind, wasted because I’d just completely vegetate on video games or books or whatever. That didn’t happen this time. There are a couple reasons for that, one being that I didn’t finish my time at work in a mad rush to get something done and the other being the list of stuff to do that I had made. That list seemed to make it a lot easier to jump in and I wasn’t just spent from the last week of work so I was able to dive in.

But one thing that I hadn’t reckoned on was that I was never quite disconnected from work – I’d lurk on Teams and a little bit on e-mail. As the time came to an end, I felt like I had to pick projects that wouldn’t poke into the time after I started work again. I had intended this break to be something of a practice session for actual retirement, and the way I ended up behaving spoiled that objective, I think.

The other thing that I knew I wanted to focus on during this time was my weight and fitness. I figured with hiking and such it’d be easy to get more exercise in during this time off and that it’d be easier to force myself to budget some time for yoga or something. But that didn’t end up happening at all. Part of that was my wife’s bursitis and part of that was the “well, in a few months/weeks you’ll be biking to work again, so…” It’s a thing I still need to work on.

But early in the summer I was learning about intermittent fasting and the research around changing your body’s physiology to delay the onset of age-related diseases. I saw that exposure to cold (particularly showering in cold water) was one of the things thought to have that effect, and that weight loss was a by-product of that physiologic change. Somehow, I managed to talk myself into it by saying “Okay, if you do this, and you start losing weight without doing anything else, then you have to keep doing it”. And I did start losing weight, so I kept it up.

For me, the key to weight loss has always been to just step on the scale every morning. It seems that just being conscious of it has a way of keeping me on the straight and narrow. When it comes to the weight loss in this summer, it could be the cold showers, but it could also be the reduced stress of not having work and it could also be just part of a long-term cycle for me that I’m not aware of. So really, the only effect that I’m sure that cold showers have is this: they save on water.

Yard Work

I’ve never been much for gardening. I think it was a reaction to my youth, when my parents would constantly make me do yard work. I think maybe it’s like fishing. When I was a kid, I wanted fishing to move faster. Now that I’m older, fishing is one of the few things that happens slow enough. Maybe the same is true for gardening and I’m just now coming to it.

I spent a lot of time pulling weeds out of the back yard (which was pretty seriously infested). I found that I could enjoy a bit of weeding and the results were pretty satisfying. Some areas of the yard were so overgrown with buttercup that all the grass was gone. In these areas and some other areas, I re-seeded. I was surprised in the variety of results I got. In one large area, the grass did tremendously well. I’ve mowed it several times. In other areas, it’s just limping along. I’m really not sure what’s bad about the bad patches, but I suspect the soil. I’ll probably have to revisit those areas next year with some better soil. The area where it did the worst is a peculiar area, because there appears to be a void under it. If I stick a piece of rebar into that part of the yard, the bar will just go right down and, in some places, literally just drop for a foot or so.

I also worked on a drainage problem in our yard. There was a pipe that takes water away from the front of the house and sends it… Well we didn’t know where it went. The pipe would generally work, but when the chips were down, it often backed up. I ended up buying what amounts to a wire on a wheel with an emitter at the end of the wire and a sensor to find it. It was more than a bit fussy as the signal didn’t penetrate the soil enough, but we were able to find it from time to time and ultimately located the “blockage”.

When I dug down to where the signal was pointing, I found a couple of concrete block-slabs – you know the kind about 9×18″ or something like that. After I dug out the top of the slabs I figured it was gonna be like opening Tuts tomb. Well, something like that. The treasure was a couple of slugs. Anyway, what I found was that the pipe was just butting into a pile of rocks. I guess the rocks were somewhat porous and allowed the water to drain into groundwater unless the ground was thoroughly saturated. So anyway I extended the pipe so that it could daylight. Hopefully that, plus some cleanup on the front end will improve the drainage in that area.

Coding

My son and a friend’s son had both expressed an interest in learning Python, and I had an interest myself so I undertook a number of projects to bring myself up to speed. First I wrote a Wordle assistant – it can play Wordle, of course, but the main mode is to rate word choices so you can do a post-game analysis. The big takeaway from the wordle experiment was that it’s a fantastic interview question. The first part, just writing an algorithm to take a user’s guess and provide the hint, is (or should be) trivially easy if you discount words with more than one of the same letter in them. (E.g. the correct hint for “enter” when the user enters “tarot” is to mark the first ‘t’ in yellow and the last ‘t’ in the word as a miss, because the answer only has one ‘t’). I suspect most candidates will struggle to come up with an elegant solution in 30 minutes. Even if they absolutely crush it, there are a lot of avenues for exploring what constitutes a “good” word to fill out the time.

After that I made up a ball-sort clone (like this) to teach myself pygame and then I started on an asteroids clone that a managed (barely) to get my son to contribute to. Sigh.

A much meatier project was revising something I wrote a couple years ago to teach myself React, a logic gate simulator for a game called Scrap Mechanic. Now, at this point, that game is pretty old and not seeming to go anywhere fast. Further, the simulator is going to be interesting to a vanishingly small number of players. Still, it’s linked from the main wiki and gets some use, and it was in a state that didn’t reflect well on me. (The UX was clunky and difficult).

My work on that project of that was colored very much by my conversations with my son in making the Asteroids game. Whenever I started talking about more beautiful ways to do something he’d just look at me like he had no idea what I was doing. “Dad, the thing works. What are you changing it for?” “Oh son, it’s more maintainable!” “Dad, you’re never going to come back to this and nobody else is going to care enough either.” “But maybe…” “Almost certainly not. It works the way it is, Dad, let’s get on with the next thing.”

Our conversations didn’t go exactly that way, but that was the spirit of a *lot* of conversations and, well, it got me to thinking that when I was in 9th grade, I thought about it pretty much the same way, and I got a lot of stuff done back then.

So the changes I made in the logic gate simulator are definitely not good examples of React. They work, and that’s good enough. When it came to that, I didn’t care that the code was nice, I wanted the UX to be nice, and I wanted to move on to the next thing.

Teaching the Kids!

First off, my daughter is not so keen on coding but is learning to drive! So we had a number of driving adventures together. My oft-neglected truck got some exercise. The funny thing to learn there was the realization that my daughter has no idea how to get anywhere. Even to visit a friend’s house that she’s been to a million times…

My son expressed an interest in learning Python and one of my friends kids did too. My son has coded in Scratch for quite some time and is somewhat proficient with it. The other boy hadn’t coded at all.

It was a miserable failure, on both fronts, I think. The boy who hadn’t coded at all found it quite overwhelming and my son, well… I tell you, I had a great advantage when I learned to code. There was no internet.

If I wanted to play a game, I pretty much had to write it myself. Now, massive distraction is just one click away, and you can’t hardly program without the internet anymore. (Because you always have to look stuff up, and that’s the only way to do it.)

I also feel that Python is a horrible language for a first-time learner of coding. But I wonder if that’s because of how I think of coding. For me, it’s all about understanding each bit of code in complete detail. For others, I think they understand it at a larger granularity. Perhaps that has its place. It’s something I really want to explore once I get back to work.

In Total…

I know a fellow who’s pushing 70 and has no interest at all in retiring. He says “I got a million hobbies and not one I want to do full time. I don’t know what I’d do with myself”. I never struggled with that. I did all million of those hobbies.

I do worry that a lot of those hobbies are best done when the weather is nice. However, I think if I had taken this break in the depths of winter, I’d still have filled my days just fine.